Conversations With A Sound Man:

Major film sound designer James Currie swirls his favourite wine – a Privee Margaux he bought in the pretty French village in 1998 and ponders on the power of happenstance.

Major film sound designer James Currie swirls his favourite wine – a Privee Margaux he bought in the pretty French village in 1998 and ponders on the power of happenstance.

His journey into sound design and his place in Australian film industry history, was pure chance following a few failures.

The multi-award-winning film man recorded the unique sound environment for the current box office hit, Red Dog, and has worked on the sound for more than 250 films in his long 40 year career. Seven were with renowned film-maker Rolf de Heer.

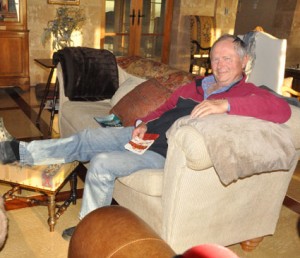

“I am actually a failed composer,’’ says James, who spreadeagles himself across his lounge before nosing and then sipping his wine.

“In Australia in the late 1960 what did you do if you were an avante garde composer?,” he asks. “I was a flautist and I had studied at the Elder Conservatorium under flute maestro, David Cubbin.’’

“One afternoon, he told me if I wanted to pursue becoming a composer I needed to go to Poland, Japan or the USSR as a musician. I said I cannot possibly think of

that; I am a poor country boy – I come from Whyalla!

“So David took me to see children’s author Colin Thiele and I said “Should I become a teacher?’’ and Colin answered “ No, not

unless you want to mark books for five days a week and only have weekends for creative pursuits’.

“This is from the man who wrote Storm Boy and all those classics.’’

Whatever was this country boy to do?

“David then said “maybe Flinders University is the place for you. You can do a film course there’ because I had done some writing and live performances at Carclew and I had had poetry

published in Meangin’s Poetry Review,’’ continues James.

“You often hear Flinders University is home for those who don’t know what to do. Well I was one, a very grateful one as it turned out.’’

However, George Anderson, head of Flinders film department recognised raw talent with a musical pedigree and soon assigned James as a recordist. “I worked on a documentary, one of a series of five-minute government informati films with Don Dunstan, which appeared on the ABC before the TV news every Friday.

“I felt privileged to be sittin and chatting with the Premier, discussing everyday topics far removed from the Government’s business of the day.

“I remember thinking at the time, surely it doesn’t get any better than this?’’

However, he reckons becoming a sound designer was an amalgam of everything that had gone before – and it opened up the world as his workplace.

“I certainly didn’t know it then or appreciate the whole alignment, but my tertiary studies proved vital in my understandings. All the bits and seemingly unconnected pieces pointed in the direction of sound design and creating soundscapes.’’

Back then James quickly progressed through documentaries and after graduation he began recording work within the fledgling film industry. It was the 1970s and he was an absolute novice in an evolving world.

“No-one prepares you for it and in those days there was no-one to teach you,’’ he recalls’

Happenstance simply had him in the right place to work the recording and mixing of sound of some of the major feature films of the 1970s when the Australian Film Industry was enjoying its Renaissance.

His first significant film was the epic Australian movie, Breaker Morant and he went on to work on such classic films as Man of Flowers by Paul Cox and Bad Boy Bubby by Rolf de Heer. “When we were filming Bad Boy Bubby, we never used the term sound design or referred to sound editors; we didn’t even know what the words meant when we started.”

Today, though, relaxing in his unique, new French Provincial home high on a hillside overlooking Carrickalinga and St Vincent’s gulf, James slips the conversation to Red Dog. At his feet sits his own hound, Maverick, a placid Wrimaraner and it is clear that the film industry has been a fortunate career for him.

James is wearing a nifty cap, emblazoned with the words “We are On A Mission From Dog’’ and when asked to explain, he laughs as he takes it off and inspects it. He says he wore it while he was making the soundtrack

for Red Dog. “All the film crew was given one from WesTrac by the producer, Nelson Woss.’’

Perhaps it brought them luck because Red Dog took $1.8 million at the box office on its first weekend, the best this year for an Australian film, says a clearly delighted James.

“The next weekend, they took even more, which is unheard of for an Australian film…and now after three weeks its around $8 million’’

He downplays his role in creating the excellent soundtrack. “ I must admit that the producer Nelson Woss, from Western Australia knew all the music he wanted for the film before the film was even made.’’

Red Dog, the film on everyone’s lips, is based on a true story of a Kelpie/Cattle dog, named Red Dog who was well known

for his travels through the Pilbara Region of Western Australia.

Director of the feel-good Aussie tale is Kriv Stenders and he was James’ connection to the film.

“Because I had worked with Kriv on two other films, Lucky Country and Boxing Day, and he contacted me.’’

“On Red Dog, I recorded the location material and special effects,’’ he says.

“Sound makes place whether it’s the hum of conversation or the rattle and roar of traffic, or that distant call of birds in the bush or that unnerving quiet of an empty stadium, or the buzz of a workplace.’’

The film features Josh Lucas, Noah Taylor, Luke Ford, Rachel Taylor and John Batchelor, but the box-office star of the film is Koko, the KelpieX cattle dog.

However, over his long 40-year career, he has won four AFI award for The Light Horsemen, and three films with film-maker, Rolf De Heer – Dingo, Bad Boy Bubby and Ten Canoes. He has also

won several overseas awards including the Golden Clapper Award for Artistic and Technical Exc ellence at the Venice Film Festival for Bad Boy Bubby.

He began building his extensive sound library which he uses in building a soundscape or illustrating an event on film.

“Sound should be fashioned to the needs and mood of the film; I did 26 minutes of what I call music in Ten Canoes as an example.’’

He pours a second glass of French wine and takes a breath; he again noses and swirls the deep crimson wine around and around revealing its long legs on the glass. Perhaps because the sense of smell is so

connected to memory, he diverts the conversation to recollections of the years he lived in France and the history of how he had bought the wine for his planned wedding with partner Olga Kostic.

“We were going to marry in Nice, but when the wedding didn’t happen, we returned to Australia with all the wine and have been drinking it slowly through the years.’’

James has known Olga since she was an eight-year-old and she was in her 20s when they reconnected and the sparks of passion flew, despite the 18-year age difference. Their home is a testament to their connection to French architecture and culture. (That’s another story, though.)

The vital question “So, what does the sound track offer to a film?’’ brings him back to the moment.

“People like Rolf say that sound is 60 per cent of the emotional content of the film,’’ he says.

“If you are doing a sci-fi film that is certainly true, if you are doing a film on romance, the film becomes the music. It certainly depends on the genre and it also depends on how you play sound. It is hard to divorce the two elements,’’ he says.

“With suspense films, you can close your eyes during the scary bits, but you cannot so easily stop ears listening. Without vision, sound stirs the imagination.

“ I think it is at least half and half. Richard Harris, CEO of the SA Film Corporation makes the point that young people will tolerate a bad picture, but they won’t tolerate bad sound.

“Now in big blockbusters, the sound tracks are huge with three speakers across the front and speakers around the walls. It is a complete envelope of experience.’’

In his long, illustrious career, which film did he enjoy doing the most? “Father Damien by Paul Cox, which was shot in Hawaii.’’

He reckons Paul Cox and Rolf de Heer are “neck and neck’’ the best film makers in Australia.

“In my mind they are quite extraordinary and they happen to both be Dutch.’’

He says he worked with “Coxy’’ for 35 years and De Heer for 25 years.’’

“Rolf doesn’t fit a mould, or dance to the usual tunes that are expected of a director. He is immersed in the intricacies of what sound can do, not only in intellectual and emotional ways, but also physical,’’ he says.

“Rolf wandered off by himself in an

operating wool store and found the sounds he wanted aned he then recorded them

from the basement under the floor where the wool presses were. This was then

constructed into trhe various melodies and sound temperaments.’’

“Film-makers do need a big dose of

luck in this industry.’’

Surely so much to celebrate with

the success of Red Dog, yet his

statement has triggered a pensive mood and he repeatedly swirls his wineglass without saying a word.

Eventually he adds: “It’s hard to celebrate within the state of the Australian Film Industry .

“The industry is run by postcodes now and I am living in the wrong postcode here at Carrickalinga.’’

Despite his vast experience, James has been without film work for 11 months as the film industry languishes. But he has recently begun location work and post production work for Rolf de Heer’s latest

film, The King is Dead, a local film shot in Croydon, South Australia.

“Picture edit has been approved by Screen Australia’’.

However did he cope without work for almost a year?

“I am coping with it by saying I am going to make a film on the longest golf course in Australia…stretching across the Nullarbor Plain,’’ he says . And his melancholy lifts to a warm smile.

“It will probably be an English co-production. You can co-produce in England, France, Argentina and Spain, Canada and Norway and USA.’’

British scriptwriter. Kit Miller –an ex Fleet Street reporter is presently in Australia working with James on script development.

His film “downtime’’ has allowed him to produce another passion of his – a primer for young people wanting to enter into the world of sound creation.

He says it is difficult for young people to enter into the world of film sound creation.

“You need pathways to learn recording and mixing, about location recording compared with post production,’’ says James. “Practical sound recording skills have been largely ignored by all

the universities.’’

Which is one important reason why James has had his biography, Conversations with a Sound Man, by Andrew Zielinski published early this year. The author,who has a Master of Arts in Film, captures James’ story and hands on his instruction on how to merge the elements of dialogue, music and sound effects as major tools in sound design.

Meanwhile, James has much to rue about the film industry today because he reckons the current funding restricts his contracts to films funded within South Australia.

“Australia has returned to the dark ages where they are selecting film crews by post code .

“It goes like this “We are the South Australian Film Corporation and we are going to put money into your film. We will say there are strings attached. You must spend 70 per cent of that money in South Australia and therefore employ South Australians whether you like it or not’.’’

“Every state does it, but I have lost three film offers because of it, because I didn’t live in the post code where the film is being made.’’

Does he see any solution to the problem of bringing more Australian films to the screen?

“We desperately need a government to re-instate the tax benefits of investing in Australian film and this is the only way we will see and hear about Australian stories, set in our landscape within our own culture up on screen.’’

Another of his sound works in Dragon Pearl, Mario Andriocchio’s film – the first Australian-Chinese co-production will hit the screen during the school holidays.

“It’s a beautiful fantasy film, but it’s a Chinese myth set in China using Australian actors,’’ he says.

Conversations With a Sound Man is available from Olga Kostic on okostic@iprimus.com.au or on www.centretrack.com.au for $34.95 AUDinc. GST.